Mine Seal

HOUGHTON COUNTY, MI – March 5, 2018 – Take yourself back to the mid-to-late 1800s in Northern Michigan when the copper mining industry was booming. Men were jumping at the chance to become a part of the prominent copper mining industry while it rose as a major industrial player in the United States. The mining took place along a belt that extended about 100 miles through Ontonagon, Houghton, and Keweenaw counties. The area was known as the “Copper Country”; This is where a large portion of the country’s copper was produced and distributed across the globe.

For over 100 years, the copper industry was the stimulus of the area, but as miners started to leave, many abandoned mines were left behind. Because the shafts and pits could be as deep as a couple thousand feet, this posed as a safety hazard for the residents in the area. In order to fix the potential issue, the mines were capped or mined off in order to prevent injuries. Yet over time, they began to cave in and brought about the risk of individuals falling in.

Today, many of the mines in Copper Country are located on large plots of land that are owned by major companies, and with the ownership of the territory comes liability for any injuries or damage that may occur within the mine shafts and pits. As of recent, two very large mines in Houghton County needed to be plugged due to the close proximity to residential areas where occupants regularly ride ATVs, walk their dogs, or go biking for an afternoon stroll across the land.

Instead of capping off the mines with concrete, rocks, or dirt, the general contractor on the job chose to use polyurethane foam to seal the pits. They chose Specality Products Inc.’s pour-in-place closed-cell foam due to its lightweight feature, eco-friendly nature, and molding capabilities, and brought in Smart Foam Industrial Coatings (SFIC) to complete the job.

RELATED Overcoming Obstacles on a Florida Roof, Fireproof Aeronautical Maintenance, Into The Wild, Greater Than Gold

“People ask why we don’t fill shafts with concrete and use foam instead,” says Bryan Scott, co-owner of SFIC. “It is because the foam won’t wash away with erosion, and since the foam is flexible, it will be able to fill cracks and crevices unlike the solid structure of concrete when it is compressed with heavy weight. The weight of concrete alone could cause the shaft to sink itself.”

What is interesting though, is that the two mine shafts that were explained in the project description to SFIC from records dated back to the late 1800s did not turn out to be what they had expected. They were documented at 18 feet in diameter with 25-foot deep sheer vertical holes. Instead, the SFIC crew found that once the mines were excavated, neither had been previously dug vertically, but rather at a 45-degree angle. One shaft contained the formation of a crater the size of a large building, and the other had the typical shape of a mine shaft but was 80-feet deep. With six days to complete the job, the SFIC team went straight to work.

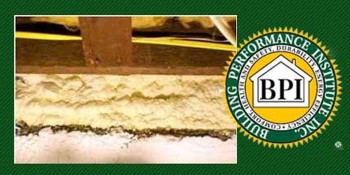

The top of the mine shaft is sealed with foam before being layered with dirt and geotextile cloth

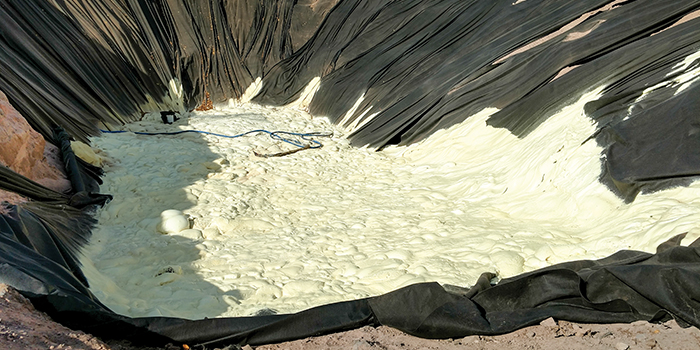

Tackling the crater-shaped mine shaft first, the three-man crew began by laying geotextile cloth inside the perimeter of the 35-foot wide, 50-foot deep hole, and sprayed the seams to keep the layers together. Utilizing a boom lift to suspend the SFIC team above and inside the mine, they essentially created a plug by installing 22 sets of custom-made SPI closed-cell 2.2 lb. pour-in-place foam with a Graco Fusion AP gun. The crew also laid a chain link fence every 10 feet in order to stabilize the foam and deter vandals from re-entering.

A chain link fence was placed every 10 feet to deter vandals from digging back into the mines

In order to prevent any falls or injuries, the crew members wore safety harnesses while in the lift, as well as steel-toed boots, hard hats, 3M fresh air masks, and gloves. Tool box talks were performed daily to ensure that the project was completed on time.

Moving onto the second mine, which required pouring 80 feet of foam to seal the seven-foot wide shaft, no one was allowed to go inside due to instability reasons. With this safety hazard preventing the SFIC crew from properly applying foam to the bottom of the shaft, they had to figure out another way to foam seamlessly from the bottom to the top. The contractor suggested to make a sled to go down into the shaft and place their guns on it while using ropes and pulleys to spray the gun. But Scott had another idea.

“I said I would make a spray foam robot. With my background in mechanics, I knew I could make a remotely operated device with basic parts including Serval gear motors, cameras, switches, relays, car batteries, and LED lights that would mount onto the sled and slide down into the shaft,” explains Scott. “When I pitched the idea, the guys looked at me like I was crazy, but only a few days later we had developed a robot that worked.”

With the issue of being unable to go into the shaft, a spray foam robot was built to take the place of a sprayer

First, the SFIC crew managed to slide down a plywood and rubber plug to the bottom of the shaft, and then utilized a control box and 100 feet of cable to send the robot down into the hole. With their innovative technology, the robot made it capable to point and spray the Graco Fusion AP gun using the cameras and a remote. Over a 12-hour period, the team installed 10 sets of the custom-made SPI closed-cell 2.2 lb. pour-in-place foam.

The robot was mounted on a sled and moved up and down the 80-foot shaft by pulleys and rope that were attached to the back of a truck

“With the robot, we were able to visually inspect each area to make sure we were able to spray each crevice and section that needed to be filled. If we were not able to figure out how to fill the shaft, the owners would have had to excavate the entire area surrounding the mine due to the underground caving in. That would have cost an immense amount of money and time,” clarifies Scott.

To seal off both of the shafts, layers of geotextile cloth and dirt were put on top of the foam in order to maintain the rural look of the residential area. “It was an interesting job, but it was completely rewarding because the owners were very happy that we were more than capable to solve the problem, innovate, and complete the job in a timely and efficient manner,” notes Scott.

As Copper Country once profited off of the mine shafts filled with illustrious pure copper metal that made men millions, today they pose a problem to society and are usually hidden from view. Some of the mines that were left behind are now part of the Keweenaw National Historical Park in Upper Peninsula, Michigan and are open as tourist attractions to the public. With such a rich history of empty mine shafts, spray foam contractors could be the ones profiting off Northern Michigan for decades to come.

Disqus website name not provided.